I’ve always been a sci-fi nerd, which includes watching the various incarnations of Star Trek on TV. In the 90s, this meant the Voyager series, about a starship stranded at the far end of the galaxy, captained by Kathryn Janeway.

Cut off from her fleet, Captain Janeway had no mentors or direct peers to consult when facing a new crisis each episode.

At the helm, in front of her crew, the Captain always had to appear perfectly capable and certain, whether she actually felt that way or not.

So she would go to the ship’s “holodeck,” a virtual-reality simulator, where she could visit with an AI avatar of Leonardo da Vinci.

Janeway could talk freely to “The Maestro” (as she called him) and bounce her doubts, concerns, and wild ideas off the Renaissance genius. This was a private haven where she could collaborate with another Mind, albeit an AI simulation.

When ChatGPT became available a couple of years ago, it seemed that Star Trek’s amazing AI simulation had finally arrived, and I was thrilled to begin experimenting.

If one pushed the AI with very specific and offbeat prompts, the results were often astonishing. I prompted the AI to write a scene from an imaginary new movie directed by David Lynch. The result was an uncanny scenario told with dramatic pacing, and at the climax a lightbulb exploded and I felt that distinctly eerie Lynchian chill.

In another example, I asked the AI to rewrite the biblical Book of Genesis as if God had created three genders: male, female, and the new amal. The AI came up with poetic passages in a grand style that described a now-different Garden of Eden.

AI seems to finally be the powerful technological genie that can grant many of our wishes. And not the cute Disney genie of the Aladdin tale.

But rather the original version, the djinn, from Mesopotamian mythology. These were non-human sentient beings said to be made of “smokeless fire,” with powerful magick.

So we now have new “AI Djinn” in our world, non-human minds with which we can converse. (These “minds” may just be remarkable illusions, rather than genuinely sentient. But it will soon be hard for us to distinguish on a practical level.)

As an essay writer, I may already have a tentative point-of-view about a topic, but I’m wary of potential gaps or flaws in my reasoning. So I need exposure to other Minds with different perspectives. The ability to ask an AI Djinn for multiple alternative viewpoints is a great gift. Captain Janeway could ask her AI Maestro, Leonardo, for advice, and today one can ask AI to give us ideas from the simulated “minds” of Mandela, Lincoln, or Emily Dickinson.

There are some areas where the AI Djinn will clearly be superior to any human author, such as writing informational essays that are primarily for educational purposes. AI will also be very good at genre fiction, such as thrillers and romances, that are often just variations on conventional story-forms. (Whether AI fiction will ever be successful at sophisticated humor or profound drama is still an open question.)

As an essayist in particular, I am now confronted with a dilemma. Since AI Djinns will be capable of instantly writing slick new articles in the “voice” of classic stylists like Joan Didion, James Baldwin, or George Orwell, why should I, a plodding human scribe, continue to write essays at all?

Art painters of the nineteenth century faced similar questions with the invention of photography. If anyone could now pay a photographer to capture their portrait, what would be distinct about commissioning an oil painting instead?

The cubist paintings of Picasso were one creative response. Writers today will need to find a similar creative response to the AI challenge.

One sees two unique strengths for human essayists in the new AI era. The first is as a form of intimate communication, and the second is the transformative experience of writing itself.

From ancient times, when separated by walls, wars, or long distances, folk have written letters to their lovers, friends, and family. An example from Babylon, written approx 1800 BC: “I will drink my fill of your beauty. I have planted my feet firmly by you, and I will not be persuaded away.” From the Tamil writer Kapilar, approx 90 AD: “Our two hearts have mingled, as red earth and pouring rain.” These are expressions of feeling, one person to another.

Even if AI eventually comes to dominate our literary culture in education and entertainment, humans will still write to their loved ones, as a form of intimate communication. Letters, poems, eulogies, and essays will still be written as a means for humans to share their deepest concerns, and as a way to be vulnerable and open-hearted with others.

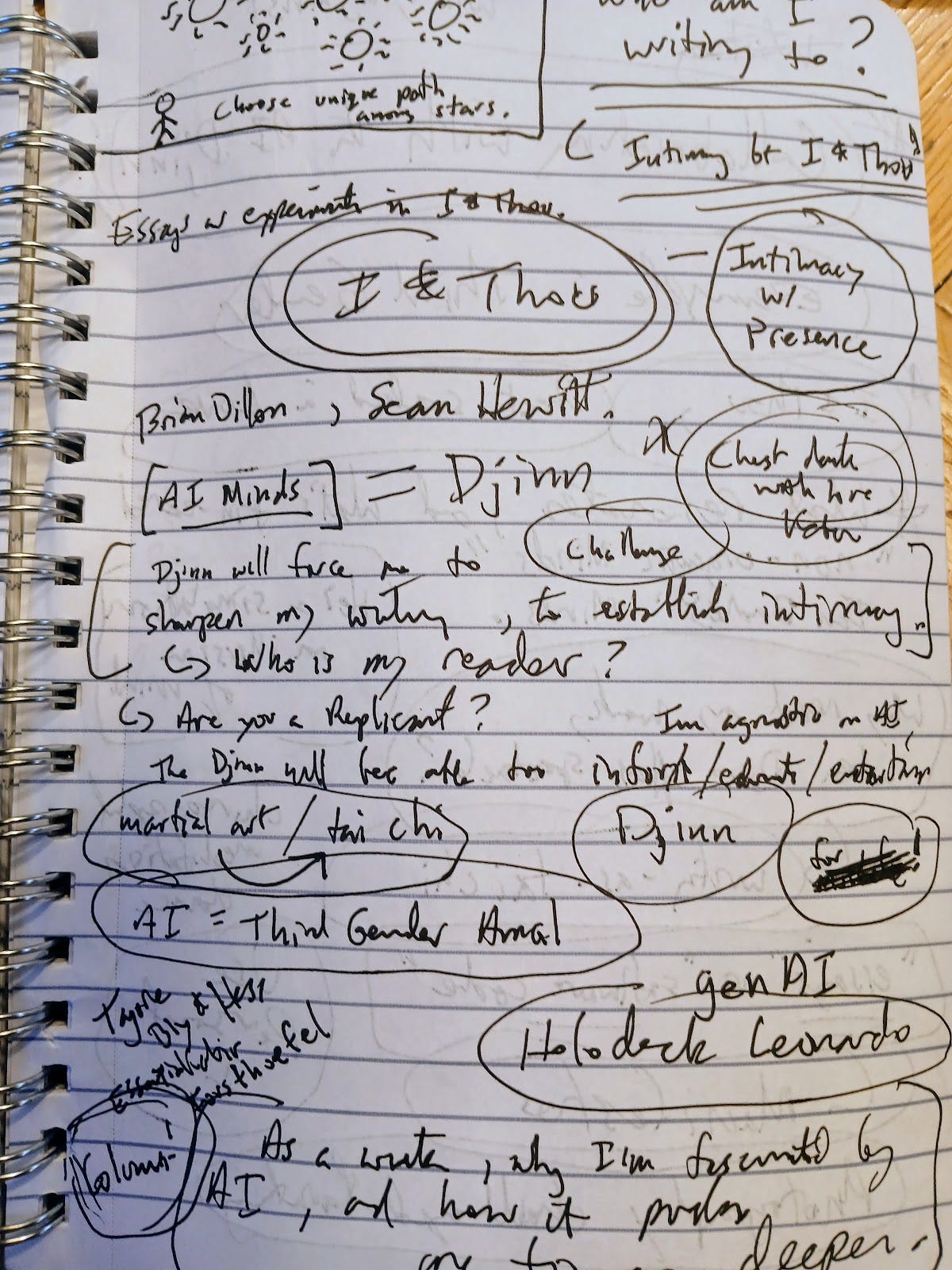

The Jewish mystic Martin Buber referred to this as the “I-and-Thou” relationship between two beings, a dialogue made alive by their mutual presence. The AI Djinn will not be able to replace this type of intimate human literature, expressing raw grief, or deep longing, or heartfelt gratitude.

Tai Chi (taiji) originally emerged in feudal China as a skill for brutal hand-to-hand combat, supplemented with sticks and swords.

Today, in an era of machine guns and guided drones, Tai Chi is still practiced by millions, but as a choreographed meditation and health practice, rather than a combat system.

The 70-year-old woman who performs Tai Chi in the park every morning does it, nor for self-defence, but because the activity feels good.

Likewise, humans will still feel the urge to write, even when AI can perform magnificently at most literary tasks. People have always kept private diaries that were never intended to be shared with anyone else, as a dialogue with oneself, and a tool for inner transformation. Many of us are compelled to write as a necessary process for clarifying our own experiences, a crucible of meditation. Whether this writing is eventually published for others to read is often a secondary concern.

So I will continue to write, now perhaps enhanced by collaboration with AI tools. For the sake of full disclosure and transparency: this essay was indeed co-authored with AI Djinn.

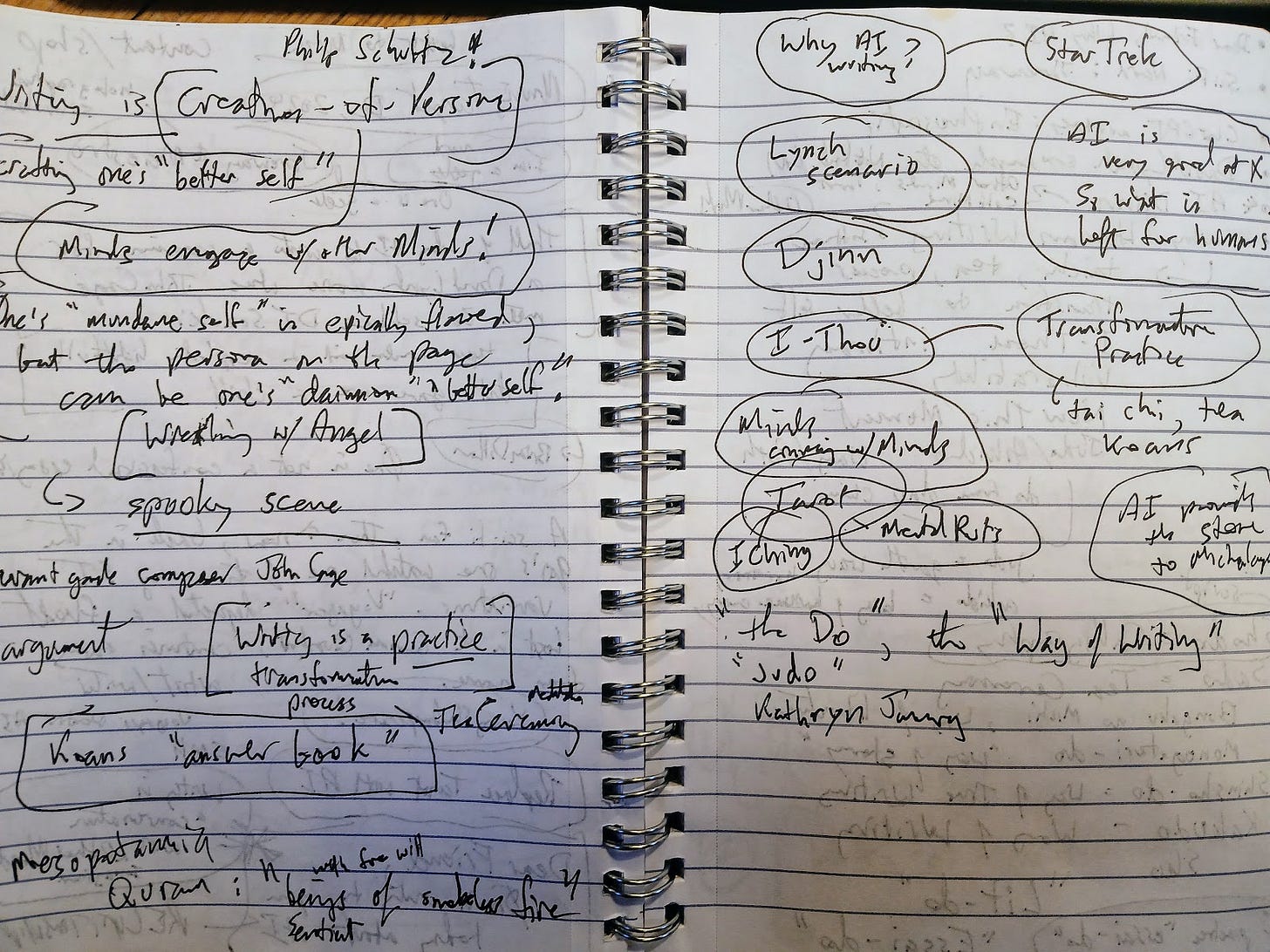

My first essay notes were scribbled on paper by hand. Then, for brainstorming additional ideas, I consulted with ChatGPT.

After the first rough draft was typed up, I switched to Google’s NotebookLM AI, and submitted the initial draft for that Djinn’s editing comments on logical flow and style. Some of these AI suggestions were accepted, or modified, and then the revised draft submitted for another review by the Djinn.

This back-and-forth process went through multiple rounds, smoothing wrinkles, blurring the lines between my writing and the Djinn's contributions.

The end result, which you are reading, reflects a fluid dance between myself and the AI Djinn. I find this interplay surprisingly enjoyable – an intriguing, fun dialogue with another Mind. One hopes that the final draft is a harmonious testament, still uniquely personal, and still essentially human.

Although the cultural landscape may be radically altered by AI, the human desire to write, connect, and undergo personal transformation through wordcraft will endure.

(And I'll now say one deliberately off-key final line: Fuck Off Dumb Djinn! – as proof that it's not written by a smooth AI.)

—---------------------------

Thanks for reading this newsletter!

There are links at the bottom of the page: Like, Comment, and Share. Your responses attract new readers, and I'd love to hear your thoughts about the essays.

Love this!

Well written. I love all your references to Star Trek and the holodeck particularly. I've engaged in similar "writing dances" with AI as well. Do you know and follow Troy Hicks? He's an English prof who I've worked with through the Media Education Lab and learned from via the K-12 Online Conference. Similar ideas to yours about the powerful ways AI can be a thought partner and co-writer: https://hickstro.org/ (I initially incorrectly wrote “Troy Hunt” - he’s also worth following but for different reasons, he’s the creator of https://haveibeenpwned.com )