Keeping your Head

choosing survival is not surrender

I recently watched ‘Will,’ an obscure 2017 series about Shakespeare’s early days in London.

Flawed and melodramatic, it never touches Shakespeare’s genius, and was swiftly cancelled. Still, I enjoyed it.

The concept grafts a 1970s punk vibe onto the Elizabethan era. When young Shakespeare says goodbye to his family in Stratford and sets off for the big city, the soundtrack brazenly plays The Clash song London Calling.

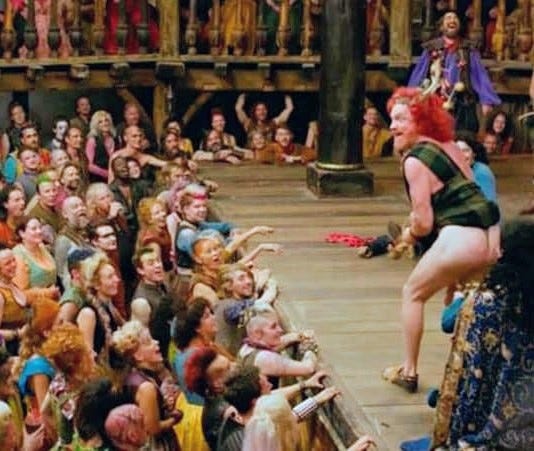

The visuals are carnivalesque; many episodes were directed by Bollywood legend Shekhar Kapur, who helmed the Cate Blanchett Elizabeth movies.

The show rightly portrays Tudor England as a police state, where the Crown relentlessly hunted enemies, foreign and domestic.

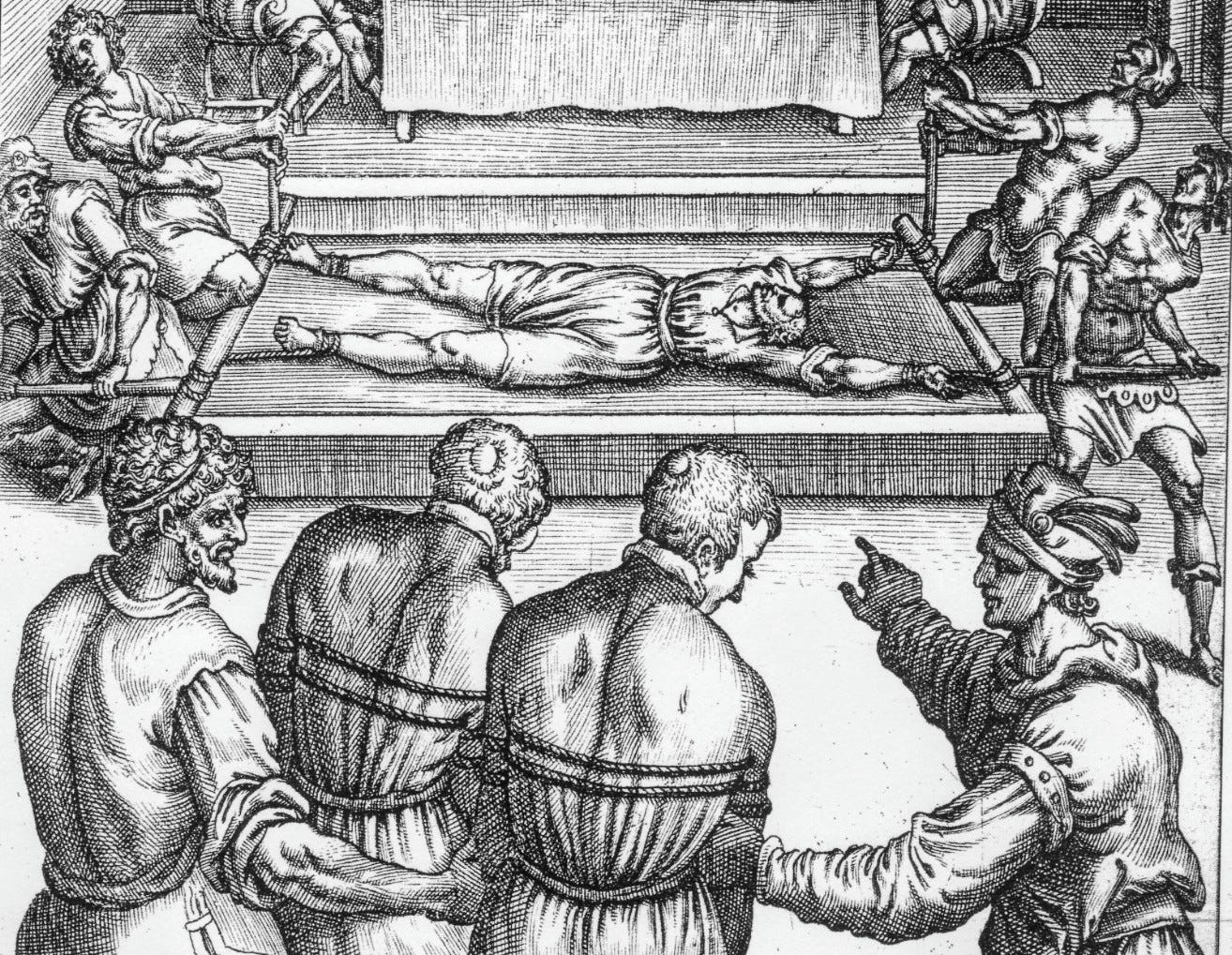

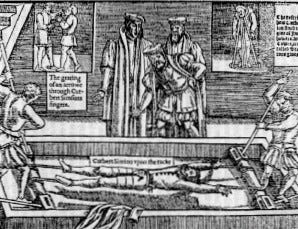

Informers were everywhere; torture and public executions were routine. Skulls hung on the city walls as grisly warnings.

The Privy Council’s chief investigator was Richard Topcliffe, who built a private torture chamber in his own house.

All playscripts had to be cleared by government censors. Shakespeare’s play “Sir Thomas More” was banned and never staged. He had written a speech pleading for tolerance toward immigrants, and empathy for exiled “strangers, their babies at their backs and their poor luggage…”

The script condemned the “mountainish inhumanity” of xenophobes. But the Crown was passing new laws to deport the Romani and Africans, and Shakespeare’s work was clearly unacceptable.

His younger colleague Ben Jonson also ran afoul of the censors. After a single performance of the satirical Isle of Dogs, Jonson was arrested by Topcliffe, and all copies of his playscript destroyed.

Worse was the fate of Shakespeare’s friend, playwright Thomas Kyd. Heretical writings were found in his home, and Kyd was arrested, tortured, and died soon after.

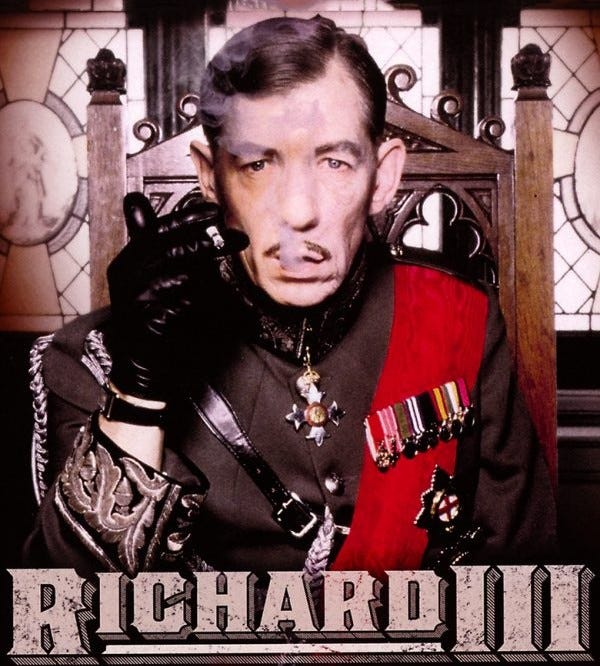

Shakespeare could not publicly stand up and proclaim that Queen Elizabeth or her successor King James were tyrants. But he certainly could depict vivid examples of other tyrants for the stage.

In “Tyrant,” Stephen Greenblatt captures power-hungry Richard III’s worldview. Richard divides people into two categories: winners or losers. And winners will always bully losers. Law and the truth are irrelevant and can be manipulated (or simply ignored) by winners. Greenblatt notes:

“Richard’s villainy is readily apparent to almost everyone. There is no deep secret about his cynicism, cruelty, and treacherousness, no glimpse of anything redeemable in him, and no reason to believe that he could ever govern the country effectively.”

Yet despite this, Shakespeare demonstrates how Richard finds willing collaborators, henchmen, and mobs that elevate him to power.

The TV show imagines a young Shakespeare who risks his life to rescue Catholic friends from persecution. But there is no evidence that the real poet ever dared any concrete dissent.

He never led street protests when his playwright friends were arrested (which would have been suicidal anyway).

He kept his head down. He kept his head, period. Shakespeare chose survival over rebellion.

Instead he wrote flattering letters to wealthy aristocrats seeking patronage, and performed his plays regularly at the royal court. He had a wife and children to support.

Facing oppression, Shakespeare chose to be a bystander rather than a rebel.

I fear that I am making the same choice. I’m not out protesting loudly on the street today either.

Like him, I’m choosing safety over courage.

A kinder view is that Shakespeare was by nature & talent an empathetic witness, and not an activist. Survival is not the same as surrender.

Honesty, in a time of lies, is its own form of rebellion.

To witness is not neutrality. It’s to refuse amnesia. The tyrant’s most important project is to make people doubt the truth, and forget history. The witness who refuses to be hypnotized by propaganda is a resistance fighter.

A tyrant thrives in the fog. He loves confusion, noise, and chaos. But true witnessing is a clean, bright signal.

Shakespeare’s stage showed that tyranny devours itself: Caesar, Macbeth, Claudius, Richard – all meet bloody ends.

By writing down essential truths, by giving them specific form, Shakespeare forged an anchor for future audiences. The tyrant builds on sand; Shakespeare sculpts in marble.

Even in a police state, the lucid gaze that refuses delusion is the beginning of freedom. And then putting the truth into words on the page.

_____________________

Thanks for reading this newsletter!

There are links at the bottom of the page: Like, Comment, and Share. Your responses attract new readers, and I’d love to hear your thoughts about the essays.

Here's my review when I saw it over a year ago:

https://chronoshake.blogspot.com/2024/06/will-2017.html