The Last Utopian

The Bomb and The Novum

Time-stream Z78:

It is 1930 in the city of Zagreb, within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. You are born to a middle-class Jewish family in a Croatian neighborhood, and your name is Darko Slesinger.

It is 1937 in Zagreb, and fascism and antisemitism are on the rise. Your father, a doctor, decides it would be prudent to change the family surname. So you are now Darko Suvin.

It is 1941, the German army has invaded, and King Peter II flees the country. Zagreb is now within the newly-created Fascist Independent State of Croatia. Your paternal grandparents and two uncles are murdered by the Nazis and their local collaborators.

As you walk home from school a bomb explodes right in front of you – its blast hurls you backwards to the ground. You are bruised and bloody, but alive.

The mental shock lingers – nine feet closer and you would be dead. You imagine a fork in the river of reality, a different time-stream where Darko has died and the world goes forward without him.

You become haunted by the potential of alternate timelines. Is there also a better world in which there is no Hitler and you are still Darko Slesinger?

It is 1943 and your family is taken to an internment camp on an Adriatic island, guarded by Mussolini’s troops. You are a 13-year-old boy with only a handful of books to read, including “Gulliver’s Travels” by Jonathan Swift, and “The Time Machine” by H.G. Wells.

Gulliver’s capture by the idiot Lilliputians mirrors your imprisonment by fascist soldiers; you realize that imaginary literature illuminates the real world.

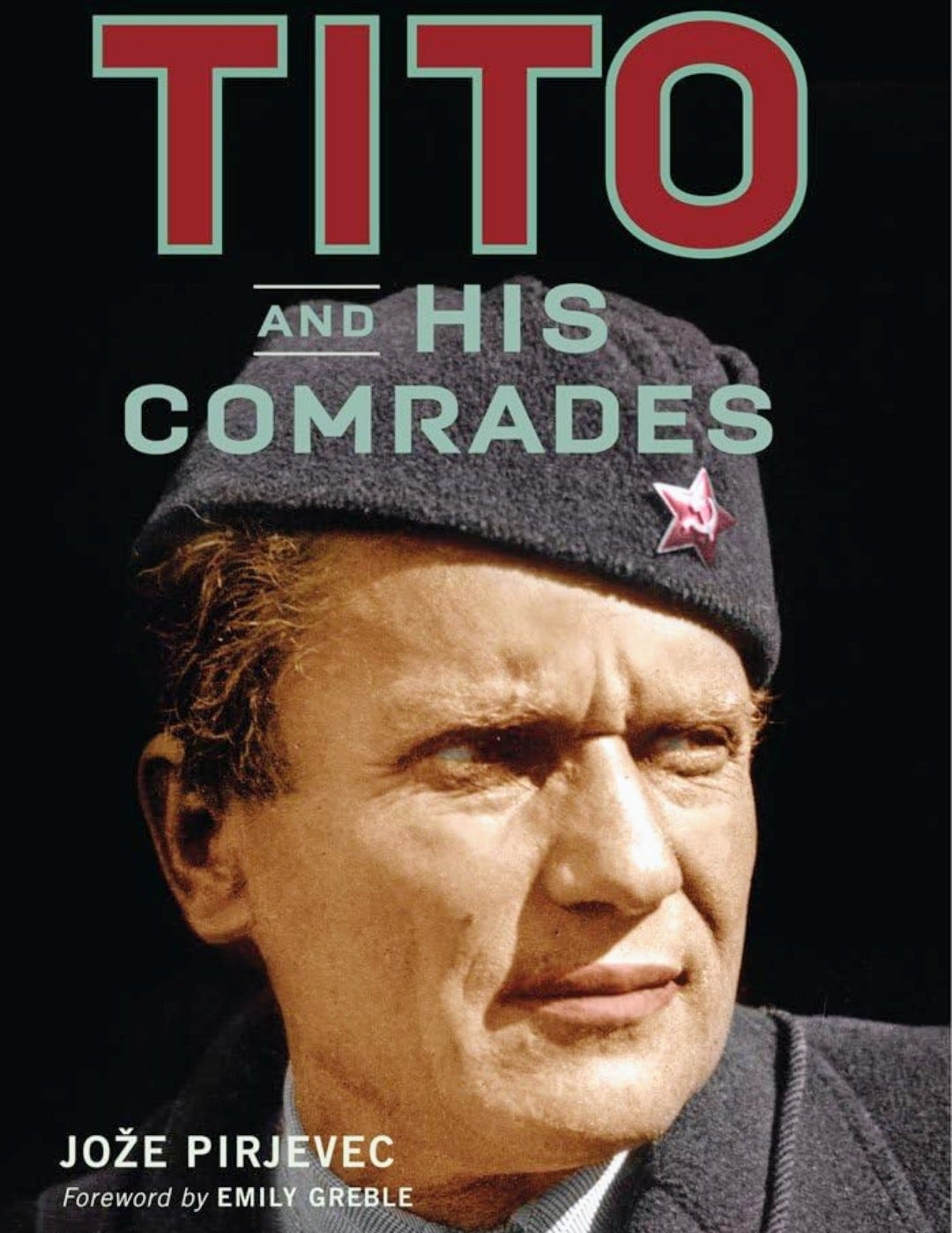

On a contraband radio you listen to BBC news reports of victories by General Tito, the heroic leader of the antifascist Yugoslav partisans.

It is 1945, and the Nazis are defeated. Upon returning to liberated Zagreb you join the Young Communist League. You idolize General Tito, now prime minister. Zagreb is within the new People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, a member of the Soviet alliance.

It is 1948. You are a student at the University of Zagreb, and an avid reader of the latest pulp “science fiction” magazines. Tito breaks from Comrade Stalin, and announces that Yugoslavia will go its own way, independent of both the Capitalist West and the Soviet bloc. Zagreb is now in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY).

You develop your English so that you can read the latest works by Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, and Arthur C. Clarke, all of which you critique through a Marxist lens.

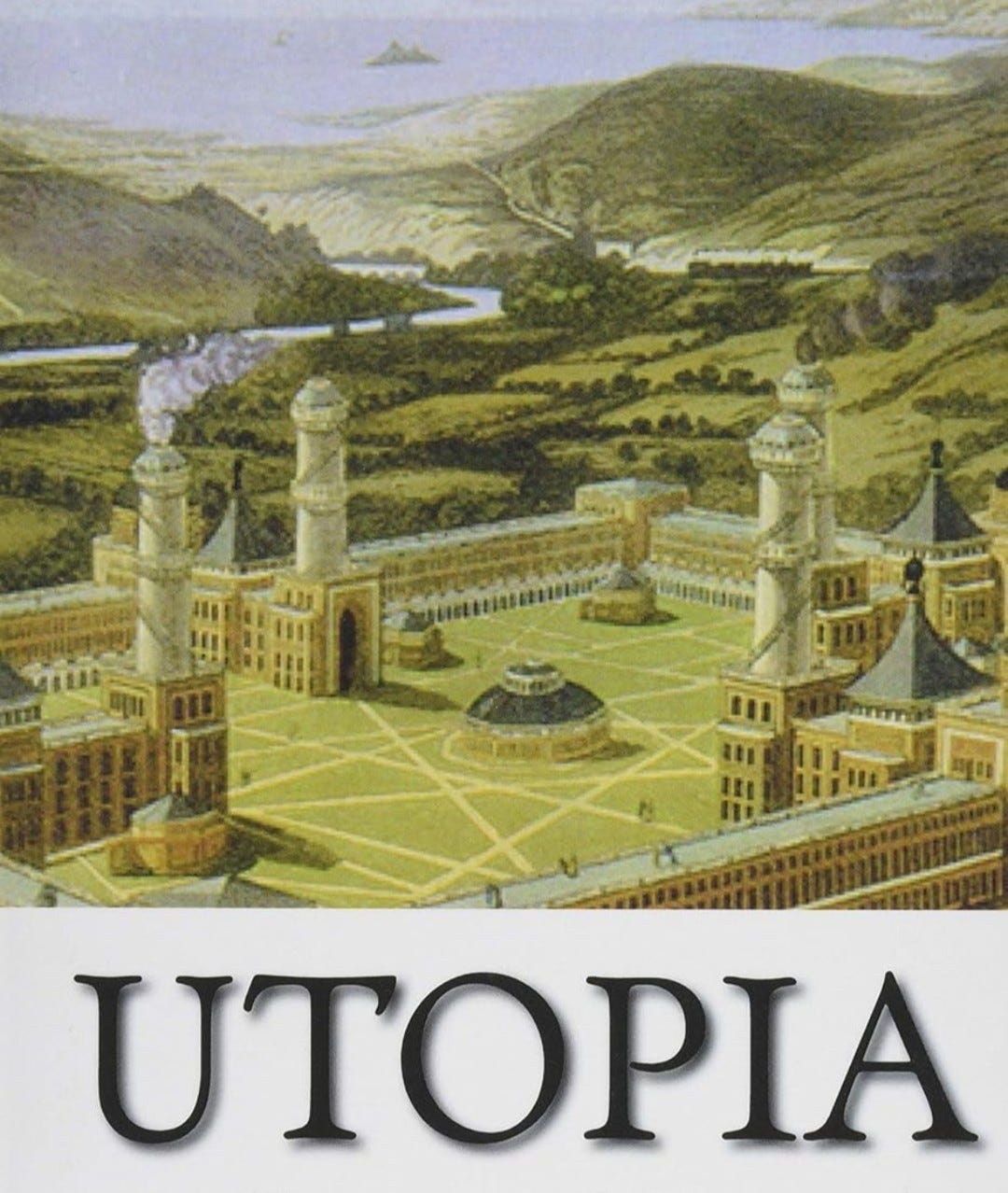

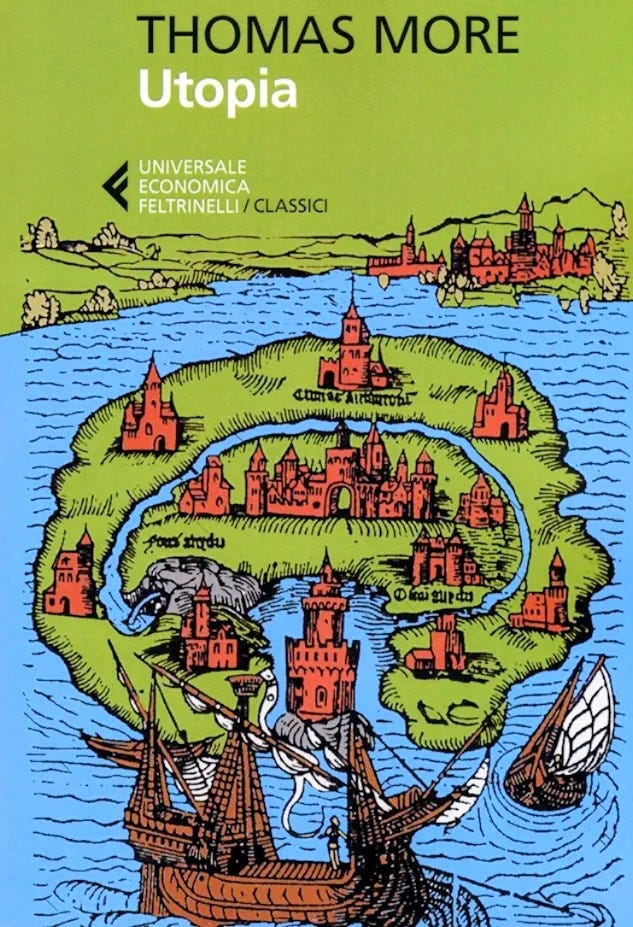

You are especially fascinated by Thomas More’s 1516 fable “Utopia” and its continuing influence through centuries of literary and political imagination.

Tito is still your hero. You are exhilarated by his vision, knowing that you are on the ideal time-stream to a utopian socialist Yugoslavia.

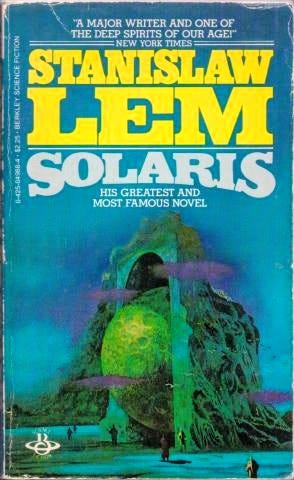

It is 1959 and you begin teaching at the University of Zagreb. You publish studies of East European SF writers: Ivan Yefremov, Stanislaw Lem, and the Strugatsky brothers.

It is 1965. Revolutionary progress in Yugoslavia has stalled: there is high unemployment, and bureaucratic gridlock. You still have faith in Marshal Tito, but think he is being ill-served by mediocre Party members.

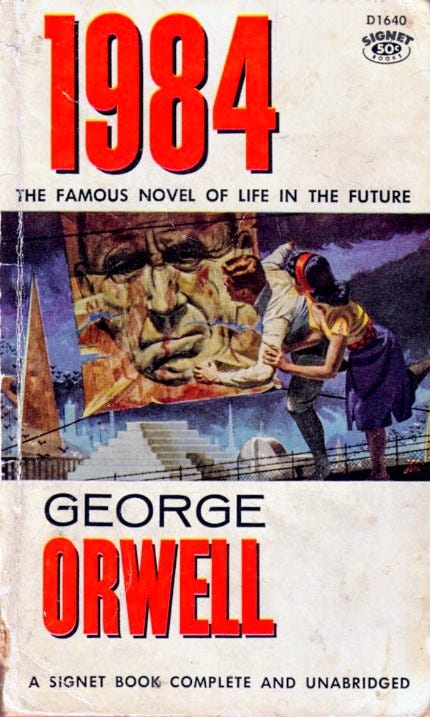

You write an article in a weekly newspaper calling for Orwell’s banned novel “1984” to be published in Yugoslavia.

It is 1969. At the University of Zagreb there are intra-Party squabbles, and a rival Lilliput faction gets you dismissed from your teaching post.

McGill University in Montreal is setting up a brand-new “Science Fiction Studies” department, and invites you to be director. Reluctantly, you leave Zagreb to start a new life in Canada at forty years of age – a Marxist now exiled to the Capitalist West.

Canada is a strange new world; you seem to have shifted to a time-stream you never anticipated.

It is 1979 and your career flourishes in the West. You publish a successful book “Metamorphoses of Science Fiction” that becomes a landmark in literary studies.

Your book argues that science fiction is not defined by starships, time travel, or alien creatures, but rather by “cognitive estrangement” – the vertigo effect on the reader as they are catapulted into mental freefall by an altered reality.

You adopt the term “novum” to describe how this estrangement is achieved within a sci-fi story. The novum forces the reader to face the implication that their present culture, their own mundane existence, could be radically different. The reader is altered by this paradigm shift: the novum opens the possibility for transformation.

The bomb that almost killed you as a child was the novum event that changed you forever.

You win academic awards and get to meet Asimov and other sci-fi writers who shaped your youth.

It is 1980, and Marshal Tito dies. Yugoslavia is now led by a series of ineffective politicians, and goes into decline. This worsens when the Soviet Bloc collapses in 1989 and everyone in the world (except you) agrees that the dream of a socialist utopia is extinct.

It is 1991 and a long brutal civil war breaks out in Yugoslavia. Ethnic conflicts become savage, and result in massacres of civilians. NATO launches airstrikes on Yugoslavia to punish the warlords. Once again, children in your homeland live in fear of bombs. You are in despair, realizing that you are on the worst timeline in the multiverse.

It is 2025 and your beloved Yugoslavia no longer exists on this timeline, having splintered into seven rival nations. You are 95 years old, retired, but still writing and posting on the internet. You warn that there is now a global ruling-class system that you have dubbed “The AntiUtopia.” The worst Lilliputians run the most powerful governments and corporations. History did not follow the path you expected.

Yet your novum endures as a liberating concept – a creative tool to conceive and forge better timestreams.

The “AntiUtopia” relies on the slumber of the crowd, but it cannot conquer the lucidity of a mind that refuses the imposed reality. The ultimate sci-fi novum is not the spaceship or time machine — it is human consciousness itself, the strangest event in the universe.

In a cold, mechanistic cosmos, the mind’s ability to perceive, awaken, and to reimagine is the true wonder.

As long as we can see the world as otherwise, better futures remain possible. This is your legacy: not a finished utopia, but the will to imagine one.

_____________________________

Thanks for reading this newsletter!

There are links at the bottom of the page: Like, Comment, and Share. Your responses attract new readers, and I’d love to hear your thoughts about the essays.

You tied intellectual history to an historical and geographical timeline and gave it a human dimension. Very powerful and well executed. Thank you for sharing.

This is amazing!

A great insights into a complex history. Clear, concise, engaging.

World's away from my quiet corner of historical events.