We Could Be Heroes

Myth and Potentiality

When I was ten years old my family moved from New York to the suburbs of Dublin, Ireland.

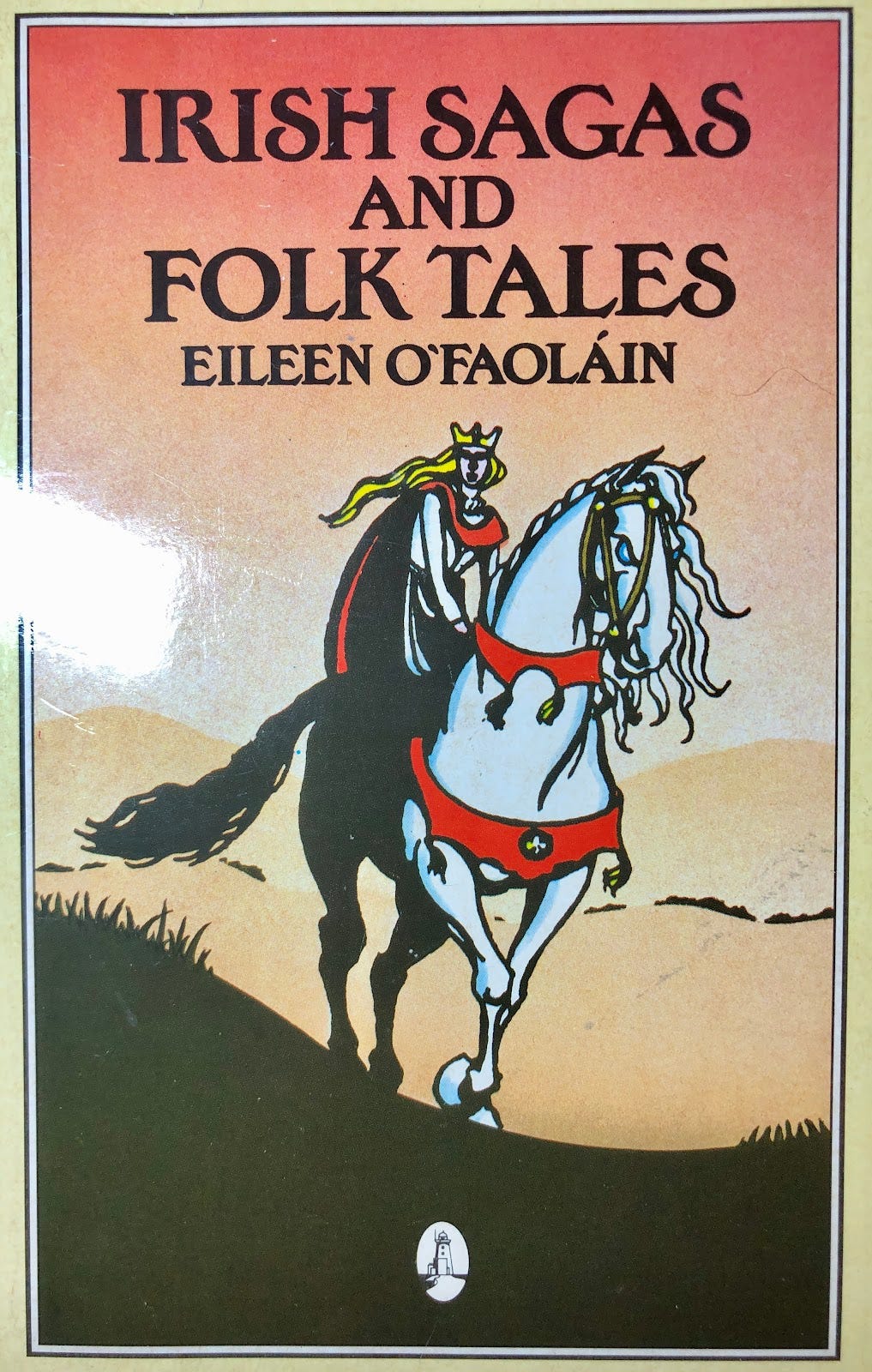

Wanting to learn about my new home, I went to the village library and borrowed a battered old children’s book called Irish Sagas & Folk Tales. The book began:

“A couple of thousand years ago there lived a people who were gods and the children of gods. They were of radiant beauty and godlike bearing, and they loved above all things poetry, music, and beauty of form in man and woman.”

Not a bad opening. I was immediately intrigued by the strange wonder-tales of the book, set in the same landscape I now inhabited.

The author, Eileen O’Faolain, had adapted the stories from the earliest written Irish literature — a motley set of manuscripts produced in medieval Christian monasteries. These are tales of an ancient pagan semi-divine tribe originally referred to as the Tuatha De (the godly folk) and later more commonly known in English as The Shee.

The original manuscripts are a chaotic patchwork of tales, impossible to categorize as neatly as, for example, the myths of Ancient Greece (which have a clearly defined Olympian pantheon).

The monks spent the workday on their official tasks, transcribing and illustrating Latin versions of Holy Scripture. And in the evenings, apparently for pleasure, they would write up ancient pagan tales in their native Irish language. Some of these were the first transcriptions of myths that had been passed down for centuries by Gaelic oral tradition.

Others were fresh inventions by the monks, allowing their imaginations to roam free. These episodes appear to be weird parables that deliberately incorporate ancient Celtic gods into the worldview of the Church (in rather the same bizarre way that Hollywood’s Marvel Studios have pulled the Norse gods Thor and Loki into its sci-fi cosmology).

Marie Heaney’s modern version of the legends describes the arrival of the Shee in this way:

“Long ago the Tuatha De Danaan came to Ireland in a great fleet of ships to take the land from the Fir Bolgs who lived there. These newcomers were the People of the Goddess Danu and their men of learning possessed great powers and were revered as if they were gods.”

In this version the Tuatha De are more-than-human but not-quite-gods. They are a new race of Noble Others.

While preparing this essay, my radio often played the boygenius band’s recent song Not Strong Enough, where the trio repeatedly chant:

“Always an angel, never a god;

always an angel, never a god…”

That phrase neatly sums up the Irish monks’ strategy when writing about the Tuatha De. The Christian scribes were uncertain about exactly how to honor their native (pagan) heritage while still keeping within the bounds of the official Church worldview.

The devout Irish monks could never state explicitly that the Tuatha De were the gods of their ancestors — instead a range of odd euphemisms were adopted to avoid blasphemy. Sometimes the Shee were described as exiled angels who had avoided the battle in heaven between Lucifer and Jehovah. Or else they were an alternate human tribe from the Garden of Eden, who had not experienced the fall from grace of Adam & Eve, and hence were free of Original Sin.

I admire the creative imagination these medieval scribes used to invent a new type of alternate humans somewhere in the gap between ordinary mortals and the divine. The Shee thus became a tribe of Noble Others — a way for humans to imagine their ideal alternate selves.

Since the Shee’s nature was in flux, they inhabited an “Imaginative Space of Possibility,” and could personify what Abraham Lincoln centuries later called the “better angels” of our nature.

The best cinematic vision of the Tuatha De doesn’t call them by that name: it’s in the depiction of the Elves in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings series. (Tolkien denied that he’d based his Elves on the Tuatha De, but there are too many similarities to be coincidental.)

In contrast to the mundane hobbits and humans, the Elves serve a role in the films as the Noble Other, representing Tolkien’s highest ideals for civilization.

The Tuatha De did not dwell high up in the sky, like Jehovah in heaven, or Zeus and the Greek gods on Mount Olympus. The Shee were here, on this landscape, almost visible out of the corner of your eye.

The Shee Otherworld was a “truer realm” that existed just slightly-out-of-phase with this mundane world. The monks may not have used the term “altered consciousness, but they implied that the domain of the Tuatha De was accessible if one could only perceive differently, with lucidity.

There are occasions in the manuscripts when ordinary humans do get a brief glimpse of the Tuatha De, or have the opportunity to cross the threshold into their Edenic OtherRealm, the Land of Youth (Tir na n’Og).

A common trope is the young man who encounters a maiden of the Shee and, enraptured, follows her into the beautiful Other Realm. Time passes differently there, and if he ever returns home again he discovers that many centuries have passed.

(One imagines a lonely monk writing these stories by candlelight in a cold abbey, always in fear of savage Viking raids, and finding wish-fulfillment in fantasies of a beautiful goddess leading him away to an enchanted land.)

A typical example is the Tale of Connla. A chieftain’s son, Connla is crossing a meadow with his father and companions when he sees a young woman approach. She calls to Connla to join her in the Plain of Delights: “It is a realm of peace, where there is no weeping or sorrow.” None of Connla’s party can see the woman, but they hear her musical voice, and fearing the Shee, they pull Connla away. She tosses him an apple before she magically disappears. For the next month Connla’s only nourishment is that apple, which is always restored whole after eating.

Finally the strange woman appears at his father’s banquet hall, again calling to Connla. This time he shouts farewell to his father, and runs off to the shore with the Shee maiden, where they hop into a crystalline canoe and sail away forever.

Throughout history, many cultures have generated stories of ideal hidden utopias — Plato wrote of the lost civilization of Atlantis, while Tibetans believed in the hidden city of Shambhala.

The power of an imagined utopia continues today, as seen in the popularity of Marvel’s Afrofuturist kingdom of Wakanda.

The fictional Wakanda is a secluded African nation that was never colonized by any European empire. Thus its citizens never experienced a “Fall from Eden” and are technologically advanced, essentially living in a utopia.

Like the Shee, the Wakandans offer an “Imaginative Space of Possibility” for the audience (especially the African diaspora) to envision idealistic alternatives to current circumstances.

In all these stories of fictional tribes (Shee, Elves, Wakandans) what fascinates us is the imaginative potentiality they open up for ordinary humans to envision and perhaps become nobler versions of ourselves.

_______________________________

NOTES:

There are plenty of modern retellings of the Tuatha De myths, but my favorite remains Eileen O’Faolain’s Irish Sagas. Although currently out-of-print, there are plenty of used copies available from online sellers. Marie Heaney’s Over Nine Waves provides a good, more adult-oriented, alternative.

Mark Williams’ excellent scholarly study, Ireland’s Immortals, tracks the cultural history of the Tuatha De as their identity morphed across the centuries.

Jim FitzPatrick’s artwork is copyrighted by the artist, and prints are available for sale directly from him: https://jimfitzpatrick.com/product-category/celtic-irish-fantasy-art/myths-and-legends/

Very interesting & informative essay (some books in there worth searching out)! A realm/people visible out of the corner of the eye puts me in mind of Susanna Clarke’s faery in Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell too. For a ‘rip-roaring’ take on Irish mythology I’d recommend Pat Mills’ Slaine.

Ha! I do agree, just shows how great myths can be interpreted in any way an author or reader wants